The 30% Factor: Exercise

30% may be an underestimation on my part, given the extreme amounts of scientific research that have been published on the value of exercise. Clear benefits have been shown for virtually every diagnostic category known — most particularly those related to conditions of aging. Even conditions where exercise would appear to be harmful have proven beneficial in moderation — back pain, arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome. Additionally, situations in which most people imagine exercisse to be irrelevant show benefits — PMS, hot flashes, multiple sclerosis, depression, anxiety, allergies, psoriasis.

For generations, our culture has become urbanized. In the process, exercise which was once necessary for survival has been displaced by cars, convenience devices, and a sedentary lifestyle. Subliminally, success and inactivity are equated in our minds.

Exercise is identified in schools with either sports (a sector of the population participates, the rest watch) or unappetizing disciplined “Physical Education.” These trends are changing, thankfully. Neighborhood gyms, runners and walkers and bikers on the roads, hiking, and home exercise equipment are becoming commonplace and socially acceptable.

The trends are encouraging, and heart disease and cancer rates reflect them. Even the decline of aging that used to seem so inevitable is turning around with light weights, walking, hiking, dancing, yoga, and swimming.

Nevertheless, studies are also unanimous that huge problems remain in motivating people to continue their exercise once begun. Men in general set goals and carry on longer than do women, but their programs rarely last more than a few months whether or not the goals are met. Other priorities push aside exercise.

Women seem to initiate exercise programs primarily in social settings — aerobics, dance, or yoga classes, walking or jogging with girlfriends, etc. Interestingly, one recent study showed twice as many women participated when buddied up with a partner. After 3 months into a 3 times weekly program, 8% continued compared to 4%. This was touted as a significant finding. My personal reading of this study is that it reflects an abysmal continuation rate — 4 or 8% continuing after 3 months is a terrible dropout rate!

My Personal Advice

It is very rare that I encounter people who disagree about the value of exercise. Everyone nods their heads in assent when I talk about it. It makes sense, but how to reset the priorities? “I have the kids, the work, the shopping….” “It is so boring and takes so much time!”

We do all live stressful lives and balance our activities poorly. Sleep (as I mention in another paper) and exercise suffer, while food, work, and socializing do not. The first step in reorienting these priorities is to experience the benefits! You must give sleep and exercise enough of a chance to show you the ease you can feel during your day — efficiency of function, stress and pain reduction, improved concentration and clarity of mind.

To do this, you need to commit to an experiment for a few months to get enough sleep and moderate exercise — and to stick to it for at least two months.

At this point, my advice departs from most programs I see. Instead of grim discipline, setting goals according to scientific studies, and working toward the “someday” when everything functions smoothly — my recommendation is to focus only on your enjoyment. Whatever type of activity you do, let it be enjoyable. Do not do any exercise you are not enjoying (except for the immediate gratification of attaining a summit or sprinting a lap).

Do a variety of activities, not just one. Do not just do treadmill, but dance, swim, lift weights, run with the kids in the park, or garden. Cross-exercising develops a variety of muscles and improves coordination and reflexes. Doing only what you enjoy keeps you focused on the important things — not just goals but meaning. The broader picture is the point.

Doing only what you enjoy also is your check against overdoing. If you were indeed straining the heart too much, or too dehydrated, or too sleep-deprived to continue on, the first thing to drop off will be enjoyment. When it becomes grim, stoic, and “just-to-finish,” you should stop.

People always ask which exercise to do. There is certainly a large volume of research literature trying to answer that question. To me, the only thing that counts is “What do you enjoy?” It can be anything from ping pong to roller-blading to dancing to yoga to running to weight-lifting…. The point is to pick things that you enjoy so that you will continue them, and if you do stop for awhile you are likely to come back to them.

Another principle is to try to do one type of activity or another five days a week. Some things (weight lifting, running) are best not to do daily, so rotating works well. Moreover, having two days a week off (or at least doing only light activity) is optimal for conditioning.

One disciplline I do consider very important: always at least suit up. It is extremely common to have days when you simply don’t feel like exercising — perhaps you haven’t slept well, stressful things are on your mind, there is too much to do, you suspect you are catching a virus. The tendency then is to just skip a day and read a book or watch TV instead. To my experience, that is a critical mistake. It is a mental rationalization that cascades over time with more and more excuses.

The trick is to always suit up — to get dressed for whatever activity you would be doing anyway, and just start. The principle, however, is always to follow the enjoyment. If there is no enjoyment after a minute on the treadmill or after the first block of your jog/walk, then give yourself permission to quit with no guilt. That happens some days.

My experience is that once we have started, the enjoyment factor does kick in and we feel like continuing for awhile. Maybe we only do half the normal program some days. That is OK, and studies prove it.

Another principle is to progress slowly, without sore muscles. If you are walking and jogging, do mostly walking, and at a casual pace at first. As you feel the joy of movement, you will jog a little. Just allow this to build. Eventually you will be jogging or running mostly, and walking very little.

All of this should not create sore muscles because it is so gradual. There is nothing wrong if you happen to push too hard one day and do get sore — no damage is done. It is just that the principle is to maintain enjoyment, which tends to droop if you are pushing to the point of sore muscles.

Fitness trainers, of course, often advocate “no pain, no gain.” That is not strictly true, in my opinion. While doing strength exercises like weights or abdominals, feeling the burn in muscles is part of the process and is fine. But that does not have to continue to the point of sore muscles over the next few days.

Tips on Specific Goals

Having said all this about enjoyment being the principle and not following grim disciplines, there will inevitably be people asking about exercise goals for specific conditions. Here is what is known according to research.

Cardiac Conditioning

Exercise is the single most important factor for preventing heart attacks, although not foolproof.

People with angina or who have had a heart attack should participate in a monitored cardiac conditioning program until stabilized.

Studies have shown that aerobic conditioning does reduce the chance of heart attack in the range of 20-25% if sustained. There are a variety of studies showing that a minimum of 20 minutes 4 days a week may be enough, but there is more concensus that 30 min 5 days a week leads to the highest protection. In addition, that is the peak. More doesn’t make any difference.

Variation in the studies may have to do with quantifying the intensity of exertion. Casual walking is not the same as vigorous walking, even though total mass is moved the same distance.

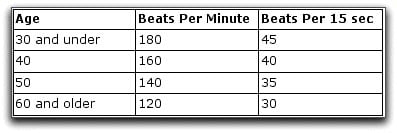

A standard that has emerged is to measure the pulse rate and aim for a “target” which is a percentage of a maximum. This is basically set by age and can be approximated by the following table:

*

The pulse rate can be determined by gently feeling for it in the carotid artery (just inside the large strap muscle on the front and side of the neck). Count for 15 sec (by the clock) and multiply by 4 to get the beats per minute.

Using this as a measure, then, cardiac conditioning for a 50 year-old would require 140 beats per minute intensity for 30 minutes 5 days a week, whether via running or weight-lifting or swimming or dancing.

Important: This is not to be attained all at once! Start very slowly and follow the body’s enjoyment level. Begin with just 5 or 10 min at a time at target heart beat, then increase duration slowly every few weeks. Getting up to 30 min might take two or three months.

To Lose Weight

Cardiac conditioning is not adequate for losing weight.

Obesity itself does correlate with increased rates of heart attack, strokes, cancer of all kinds, diabetes, hypertension. Correlation, however, does not necessarily equal causation. I am still searching out studies that identify obese but fit people and their risks for these diseases. The only thing I have seen is the value of exercise in reducing cholesterol in obese people, but that is known not to be a good correlate with cardiac risk.

In any case, whatever it takes to lose weight does seem to reduce risks of all of the above diseases, so it is a worthwhile effort. However it is very difficult.

Obesity is largely hereditary, but it is clearly related even more primarily to exercise. A common assumption is that it is caused by overeating, but lack of exercise may be an even more powerful component.

Exercise burns calories and dramatically lowers insulin levels in the blood stream. Insulin converts carbohydrates to cholesterol and fats and then deposits those fats into cells (including arteries). Thus, exercise transforms metabolism so that calories consumed are utilized more efficiently and converted less into fat.

The bad news is that the amount of exercise needed to lose weight is 60 minutes a day for 5 days a week! [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][This can be done in more than one session a day, but the total must be 60 minutes] Moreover, the intensity must match the table above.

So, a 50 year-old person must sustain 140 beats per minute for 60 minutes 5 days a week. That will hopefully reduce weight at no more than 2 lbs a week [in order to avoid triggering a “rebound” that results in regaining all the weight plus 10% more, within one year]

Osteoporosis

A whole industry has been built around osteoporosis, with fancy machines trying to diagnose it early enough to prevent fractures that can lead to debility and death in older age. Meanwhile, calcium is touted even though it has an insignificant effect, and estrogen was finally disproven after a spell of extreme hype.

However, it has long been known that bedrest and weightlessness (NASA) are the primary causes of osteoporosis — in short, lack of physical impact on bone.

It has been known that swimming has no effect in correcting osteoporosis. Walking was supposed to help but later studies called that into question.

Finally, a huge prospective study of nurses on the East Coast clarified the issue. They were asked to do at least 5 jumps a day, and were then followed with bone density studies for decades. Many did up to 50 jumps a day in order to lose weight, etc., but bone density maxed out at 5. This was an actual increase in bone density, not a mere slowing of the rate of reduction.

Last year, an Israeli study confirmed the same principle. It found also that walking in itself does nothing to bone density, but they found that running for only one minute of the walk was enough to actually increase bone density.

In retrospect, susceptibility to osteoporosis in elderly women is not related to bone density at all as to fracture susceptibility in people who are sedentary. The best prevention is to be physically active in all ways. Bone density sometimes correlates but is not really a causative correlation.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]